Playing the bagpipes is exhausting. You just have to fight with the instrument long enough to be able to tame it at some point and make music with it. It happens that such and similar ideas of one’s own instrument as an opponent to be conquered are cultivated by fellow players and confirmed by individual learning experiences. Does it have to be that way?

Joachim Schiefer answers this with a clear ‘no’ and points out an important connection: ‘If I have the idea that “this is difficult”, then I automatically adopt a corresponding posture that is unfavourable for playing.’ The professional cellist is of course aware that the instrument should be in a good, playable condition and that learning to play it can also involve effort and endeavour. At the same time, however, he knows that in many cases the path to music is unnecessarily arduous and sometimes even obstructed.

Help through Dispokinesis

It was in the mid-1990s that Joachim Schiefer himself got into difficulties: an inability to play due to focal dystonia – also known in its specific form as musician’s dystonia. This is a neurological disorder that interferes with the execution of previously learnt, complex and precise movements. A catastrophe for the professional musician. At first he was unable to find help. His despair grows. Then he came across the therapy form of dispokinesis, which was largely developed by the Dutch pianist and physiotherapist Gerrit Onne van de Klashorst (1927–2017) in the 1950s. Dispokinesis could be described as a movement pedagogical training concept that – simply put – focuses on the psycho-physical prerequisites for making music. Through an intensive examination of posture, breathing and movement in particular, as well as inner attitudes and mental processes, the aim is to maintain, improve or regain the ability to play and express oneself musically.

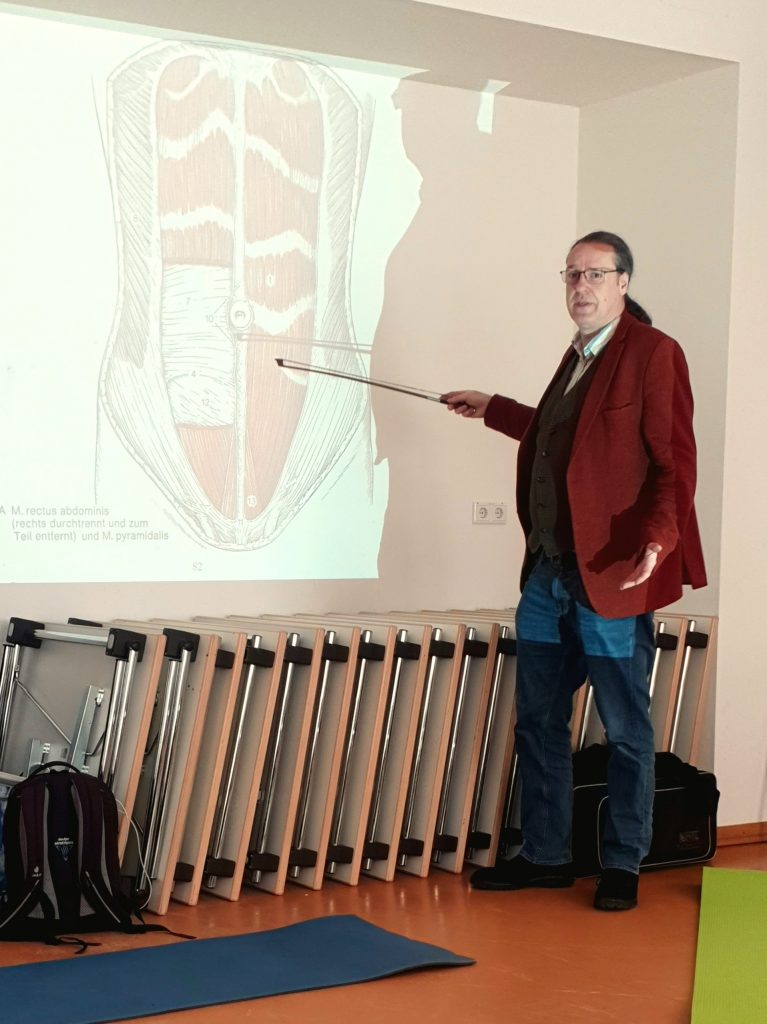

Schiefer made contact with van de Klashorst at the time and found help. He becomes his pupil and completes a three-year training programme to become a Dispokineter in Düsseldorf. In total, he underwent a seven-year learning process in which he fundamentally changed his motor skills on the cello. He eventually regained his unrestricted playing ability. Today he gives courses, workshops and seminars on various aspects of musician’s motor skills. As part of his teaching activities, he is a regular guest at the Dudelsack Akademie in Hofheim am Taunus. These events focus on basic physical correlations and the influence of body and instrumental posture on motor skills when playing the bagpipes.

Around ten participants…

have gathered on this Saturday morning in April in a seminar room in the historic cellar building in Hofheim. In addition to their instruments – Highland bagpipes, smallpipes, various medieval bagpipes – they are packed with woollen blankets and camping mats. Over the next seven hours, concepts such as ‘feeling’, ‘imagination’, ‘stability’ and ‘posture’ will play a central role, and the participants will have the opportunity to train their body awareness and scrutinise their mental dispositions through practical exercises. ‘What is my basic feeling when I play?’ is such a seemingly simple question, but once you get into it, it can open up unexpected insights into your own musical practice. Because it draws attention to an often blind spot. Is it effort, excessive demands, discomfort? Or is it rather a feeling of elation? Perhaps joy, security, happiness? ‘We always play from an individual feeling,’ says the Dispokineter from Wuppertal. You have to know the feeling that makes something work and learn to bring it under control. Then it can even be specifically created and used, for example to reduce nervousness in unfamiliar environments.

From imagination to movement

Joachim Schiefer is particularly keen to emphasise the relevance of imagination and posture for an appropriate ability to move when making music. Both – posture and conception of movement – have a decisive influence on motor skills on the instrument. A vivid example: as a pianist, his teacher, van de Klashorst, cultivated the idea of floating hands on the piano in order to promote fine motor functionality, recalls Schiefer. Looking at the instruments in this workshop, one could say that anyone who thinks ‘I’m holding the chanter in my hands’ is perhaps already making life difficult for themselves because they are following an image that can cause tension and overly firm grips. And if you are looking for a possible alternative to ‘gripping’ and ‘holding’, you may be better off with ‘touching’.

Of course, a bagpipe could also be seen as a piece of sports equipment that requires a great deal of physical effort to make it sound. However, as Schiefer points out several times, low-fatigue playing and technical finesse can only be achieved through energy-efficient fine motor skills. In addition to the right mindset, this also requires freedom in the upper body, which is guaranteed by a stable body centre. Lying on blankets and mats, the participants try out hidden muscle groups in order to realise the prerequisites for their physical stability.

In the course of the event, it will become clear what the specific challenges of these instruments actually are. In a nutshell, it is the necessary separation of gross and fine motor processes, which should run synchronously but not interfere with each other. For right-handers, this is particularly evident in the left arm. While the left arm exerts constant pressure with gross motor actions, the hand requires the greatest possible freedom for precise movements. The short guide to decoupling these processes could be: stability in the centre and training the fine motor skills of the hands, i.e. avoiding unnecessary movement activity (stretching the fingers over the holes) with as little effort as possible. ‘In order to have control over the holes, it is not necessary to press your fingers onto them with several kilograms of weight,’ Schiefer points out.

Lesson about easiness

Occasionally, the lecturer steps out of the thematic framework of the workshop and demonstrates the ability to connect to other issues. For example, when he identifies the general devaluation of feeling and intuition as a social problem or laments the increasing loss of fine motor skills among young people. However, such judgements are the exception. Schiefer rarely says ‘That’s the way it is!’, his offer is rather an ‘it can be’.

It takes a while for all the details about psychological experiences and anatomical aspects to come together to form an overall picture. The further the event progresses, the more focussed and thoughtful many of the participants become. It will then be up to each individual to take away from the wealth of information and knowledge and integrate it into their everyday musical life in a way that is helpful to them. In any case, this day should have opened up a new horizon, in which the handling of the musical instrument appears from a new perspective. One participant confirms this as we descend the heavy wooden stairs of the basement building to the ground floor after the seven-hour course. In many teaching situations, the focus is – understandably – on the music and the fingers, while the whole psycho-physical complex that makes musical activity possible in the first place receives little or no attention, she reports from her own experience.

However, the greatest benefit of this training course entitled ‘The body, our most valuable instrument’ may be that it is actually about more than just handling musical instruments. It’s about an attitude to life. It’s about how we present ourselves to our surroundings on a daily basis – as battered bundles of nerves or as positive, cheerful creatures who, in the best case scenario, can even create something like music.

Yes, if it was easy. Making music, life. A pipe dream for sure. But perhaps more of it can be realised than we allow ourselves to assume.

Joachim Schiefer

Thomas Zöller