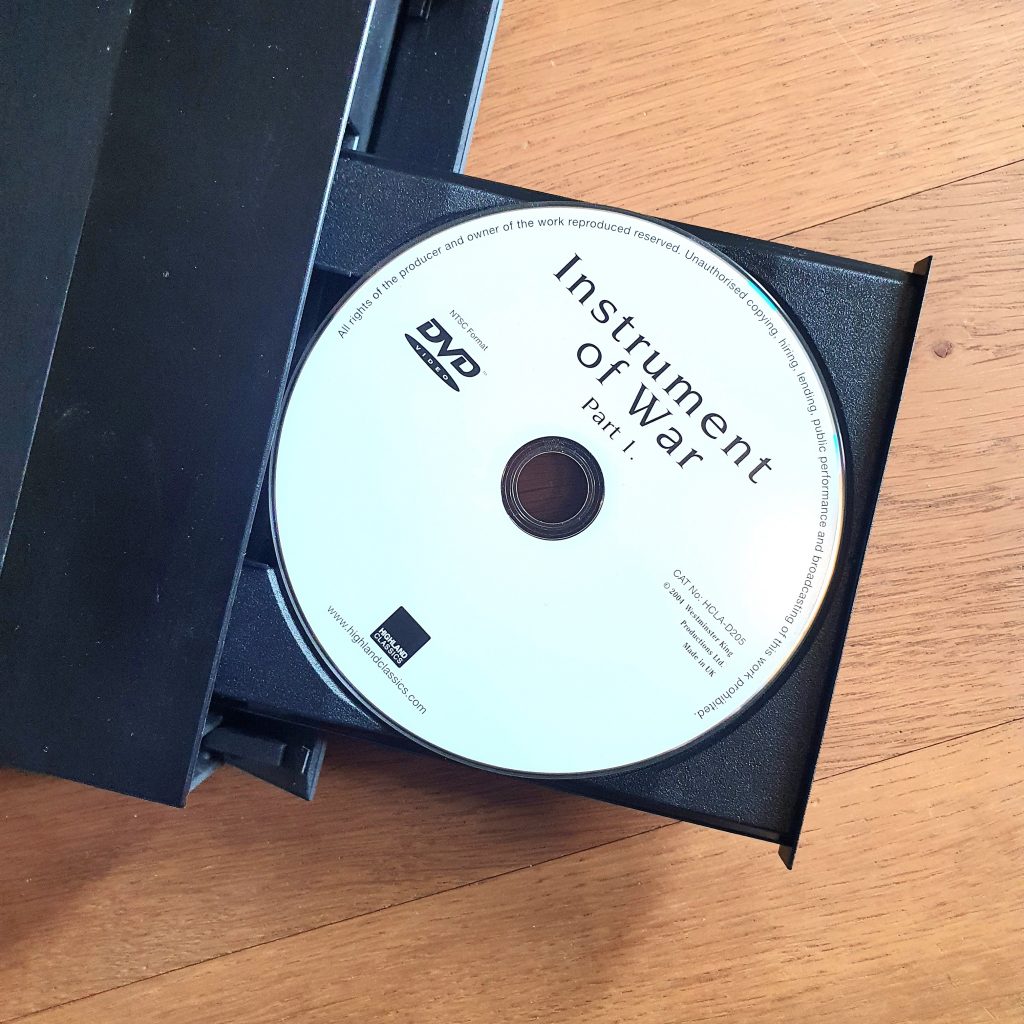

It must have been around the year 2000 when I saw the film documentary The Powerful Story of the Great Highland Bagpipe for the first time, played on a VHS player. The media revolution was in full swing, and so the two-part documentary was released a short time later on DVD, the medium of the future. Apparently, the opportunity was favourable to adapt the cover design and give it a more martial touch. After all, former the subtitle Instrument of War was given a prominent position on the narrower sleeves. In terms of content, this shift in emphasis towards the imposing war label was entirely justified.

The film tells a musical war story, with a few side scenes – from Scottish rebellions against the crown in the south, to the campaigns of the British Empire in the 19th century and the mechanised nightmares of the two world wars. After the now antiquated discs reappeared in forgotten boxes some time ago, the search for suitable players began. VHS was lost. But compatible hardware was eventually found for DVDs.

‘I gave me courage, and I gave them courage’

The film begins with an impressive quote, the origin of which the viewer is unfortunately left in the dark: ‘Music and war are inseparable’. A strong assertion. Whether it is true is hard to judge. Doubts are justified. But that’s probably not the point here. It’s more about the effect of an initial statement that sets the tone for around two hours of film about despair and honour, glory and pain, morality and heroism, about fields of rubble, piles of corpses and traditions.

Among the most remarkable passages are the accounts of veterans of the First World War, many of whom appeared in front of the camera for the documentary. Perhaps the greatest merit of the filmmakers lies in preserving their accounts, especially as none of the people who spoke – most of whom were over 100 years old at the time of filming – are likely to be alive today.

On several occasions, the camera paces through aristocratic military picture galleries – glossy testimonies to the 19th century and at the same time illustrative devices that radiate a venerable light. Yet these scenes remain comparatively remote and abstract. In contrast, the film unfolds its fascinating immediacy and expressiveness in those parts in which the contemporary witnesses have their say.

‘Suddenly I heard the bagpipes, I wanted to get into the bloody war’

A slight irritation arises as the music plays during the end credits. This may be due to the simultaneity of affirmative pathos and critical commentary. Both pervade the film and sit side by side without being resolved to one side or thematised as opposites. There are places where it is debatable whether the threshold of glorification has been crossed. At the same time, there are statements that reveal a rather distanced relationship. In the end, the viewer is left alone with these tensions and dissonances. He can take the failure (or refusal?) to make a clear statement as an invitation to form his own judgement.

‘I had to’ ‘We had to’…

are recurring statements made by those involved in the war, as if to make it clear in retrospect that the insanity of the events was not their responsibility. The film, produced in 1997, has itself become a historical document. It was made at a time when the belief had spread across an ageing continent that the world’s major lines of conflict were in the process of being resolved. Things were to turn out differently.

Perhaps a media company will be found to continue this story. Would they talk about ‘instruments of war’ with the same emphasis, while disillusionment has set in that trenches are now being dug again in Europe?

It’s worth watching the film again. Even if it’s only because of one statement that can summarise the entire content: Whatever happens, we have to carry on somehow. Music can help with that.